From yarn to fabric

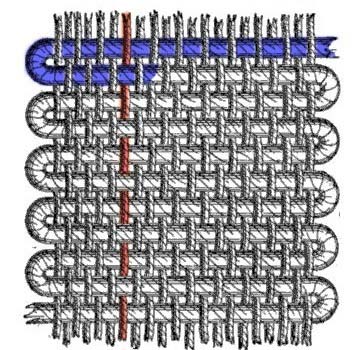

Weaving involves interlacing weft yarns with warp yarns (the latter are the ones that are stretched over the loom). The manner in which the yarns are interwoven defines what is called the ‘weave’. The most widely used weave is 'plain’ weave (also known as ‘tabby’ weave) in which each weft yarn is passed alternately over and then under the warp yarn, alternating in each row.

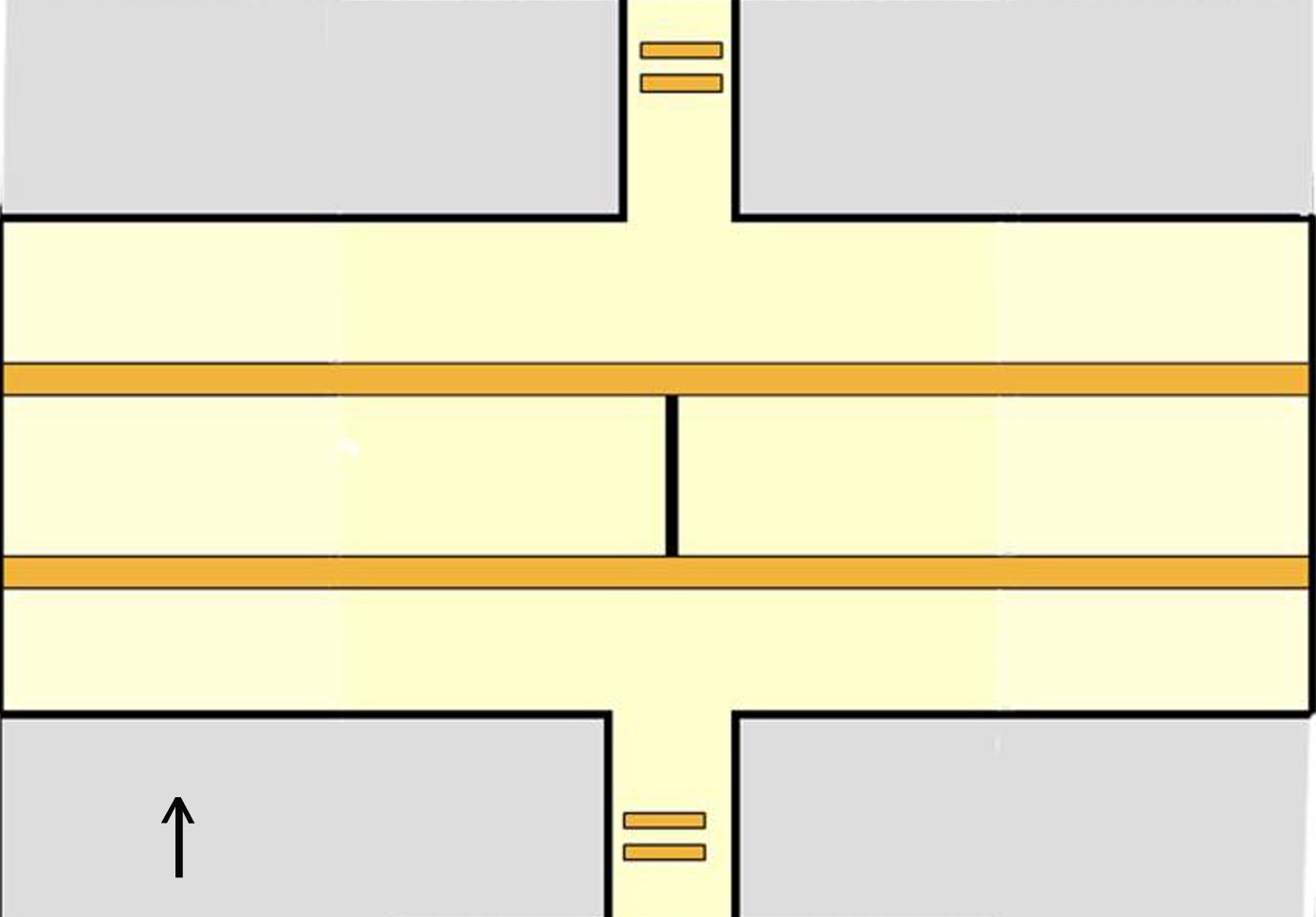

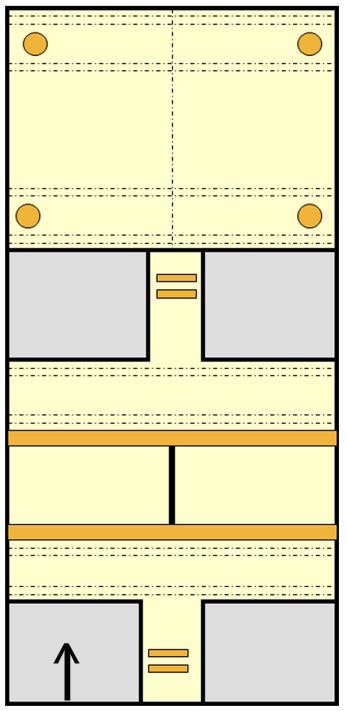

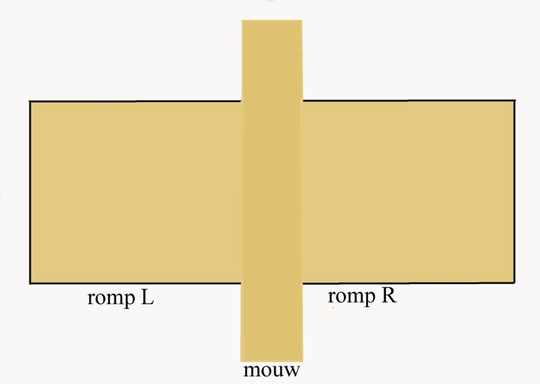

Whilst the wool and linen weavers of Late Antiquity both worked on vertical looms, their techniques and methods were rather different. Both wove their tunics with a horizontal warp. Once the fabric of the tunic was finished, it was taken from the loom and turned 90° to make up the tunic. In order to have the correct orientation of the motifs that would decorate the tunic, the weavers obviously had to take account of this last operation. As far as the clavi were concerned, when they continued down the back, the design had to change direction at the neck edge.

Drawing: Chris Verhecken-Lammens

Drawing: Chris Verhecken-Lammens

Linen weaving

For weaving linen, the general structure is a warp-faced tabby weave with a higher number of warp threads per cm than the quietly stretched weft yarns. A large part of the Fill-Trevisiol collection of textiles uses a simple linen warp, S-spun (twisted to the right), a technique used for tunics and furnishing textiles. The selvedge of the fabric was simple and seldom strengthened. Sometimes, the extremities of the warp were knotted with an additional yarn and enclosed in a seam.

The collection includes numerous decorative fragments in tapestry. Some are woven within the linen itself (so-called ‘inwoven’) and in this case, the weft yarns completely cover the warp yarns. This necessitates regrouping the warp yarns on the width of the part to be decorated and switching from a warp-faced tabby weave to a weft-faced (Louisine) weave.

Photo: Chris Verhecken-Lammens

Drawing: Chris Verhecken-Lammens

Other linen fabrics present warp threads that are plied S2Z (two S-spun yarns which are then twisted together in a Z, i.e. to the left). Such pieces were woven separately and sewn onto a support. This technique had already appeared at the time of the Romans, but remained rather rare until the Islamic period. It would be used to weave the decorative parts of a garment and these were then fixed onto the tunic fabric.

For tunics woven in shape and in a single piece, a large loom was needed. For linen tunics, another technique consisted in assembling two or three pieces woven on a narrow loom. This method meant less waste of the non-woven warp yarn on the front and back panels of the tunic.

Weaving wool

To weave wool, the weavers kept the warp yarn tightly stretched. Woollen yarns had a lower density (between 8 and 12 yarns per centimetre) than was the case for linen. The most common binding system was plain weave, in which the weft covered the warp almost completely, a so-called weft-faced tabby weave. For each piece, the appropriate length of wool had to be stretched over the loom. To weave a tunic for an adult, the width of the loom could exceed three metres.

After the weaving had been completed, the ends of the warp yarn were finished with a plied selvage that brought together all of the loose ends to form a strong edge, the finishing border. In this way the four sides of the woollen textile were protected from fraying.

Drawing Chris Verhecken-Lammens

FT 56. Photo: Chris Verhecken-Lammens

The various techniques

On most of the weavings in the Fill-Trevisiol collection, the decorative elements are in tapestry. In this technique, the dyed weft yarns are introduced following the design and interrupted when the colours or design change.

However, there were also other techniques of fashioning a textile. These included varying the thickness or the direction of the weft yarns, flying thread (use of an additional yarn turned around a warp yarn creating a motif), brocaded fabrics (additional wefts introduced locally into the ground weave to create a motif), design by ‘floating’ (additional linen wefts in woollen braids) and looped pile fabrics (loops created with additional linen or woollen wefts into the ground weave).

FT 156. Photo: Chris Verhecken-Lammens

FT 142. Photo: Chris Verhecken-Lammens

Among the latter, a very rare technique in late Antiquity is called ‘warp pile velvet’, in which the loops are formed by the additional pile warp. The Fill-Trevisiol collection has a fragment in warp pile velvet (see FT142), with purple Z-twisted yarns in the tapestry, making this a truly exceptional piece.